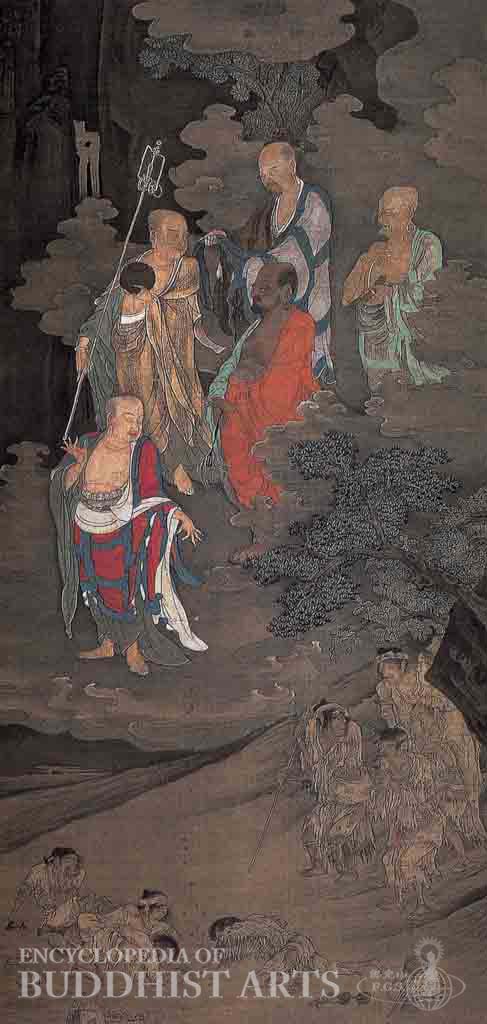

Five Hundred Arhats - Stone Bridge of Tiantai

Ink and color on silk

Five Hundred Arhats - Ascending Auspicious Sign

Five Hundred Arhats - Offering from Monks and Devottees

Five Hundred Arhats - Patching Robes

Five Hundred Arhats - Giving to the Poor and Hungry

Five Hundred Arhats - Receiving Offerings from Foreigners

Five Hundred Arhats - Witnessing Light from a Relic

Five Hundred Arhats - Meditation in a Cave

Five Hundred Arhats - Manifesting as Avalokitesvara

Five Hundred Arhats - Classic Miracle

Five Hundred Arhats - Feeding the Hungry Ghosts

Five Hundred Arhats - Laundering

Five Hundred Arhats - Admiring a Painting Beneath Trees

Five Hundred Arhats

CHINA; Southern Song dynasty

Yishao, a monk at Hui’an Monastery, raised money to commission this set of images in 1178 of the Southern Song dynasty. The project took nearly ten years, and resulted in 100 paintings, which were subsequently brought to Japan. Six of the paintings were lost and then recreated in 1638 of the Edo period. Twelve were taken to USA during the Meiji period (1868–1912); ten are kept in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and two are in the Freer Gallery of Art, USA. The remaining 82 paintings are kept at Daitokuji Temple and have been listed as Important Cultural Properties of Japan. Inscriptions on the paintings name the artists, Lin Tinggui and Zhou Jichang, as well as the donors who sponsored them.

Most of the paintings show five Arhats accompanied by attendants and other figures. The Arhats are portrayed as Dharma protectors who engage in both everyday activities and miraculous feats. They discuss the Dharma, patch their robes, meditate or read sutras. Some receive offerings, while others give to the poor. There are also images of Arhats feeding hungry ghosts or defeating demons.

Among the paintings, Classic Miracle depicts the Arhats converting non-Buddhists, while Patching Robes and Laundering show the Arhats engaged in the daily activities of monks. Stone Bridge of Tiantai depicts the natural stone bridge across the cliffs of Tiantaishan, blocked at the far end by an impassable rock. It was said that the residences of the Five Hundred Arhats lay beyond the bridge.

The two artists, Zhou and Lin, are also included in the images. In the Manifesting as Avalokitesvara, an Arhat is depicted as a manifestation of an Eleven-Headed Avalokitesvara. In Offering from Monks and Devotees, the monks and devotees are seen holding offering objects in front of the Arhats.

The backgrounds are primarily painted with dark ink, while the figures and their robes are painted with bright colors. The strokes are delicate, typical of Southern Song dynasty artworks. The style is uniform in most of the paintings, although Zhou’s lines are more fluid and elegant, and Lin’s strokes are more powerful. The names of the painters are not recorded in any historical documents, so it is presumed that they were commoners rather than court artists.

For more details, go to the Encyclopedia of Buddhist Arts: Painting A-H, page 242.

Cite this article:

author = Hsingyun and Youheng and Youlu and Wilson, Graham and Manho and Mankuang and Huntington, Susan,

booktitle = {Encyclopedia of Buddhist Arts: Painting A-H},

pages = 242,

title = {{Five Hundred Arhats}},

volume = 14,

year = {2016}}